Your cart is currently empty!

Aid to Africa: Short-Term Relief versus Long-Term Capacity-Building

By Nathan Kiwere

Since the mid-20th century, international aid to Africa has been both a hopeful response to poverty and an unintended source of dependency. The debate around the effectiveness of foreign aid in Africa centers on whether it provides sustainable benefits or inadvertently hinders the continent’s progress. Unfortunately, much of this aid has historically prioritized immediate relief efforts rather than long-term capacity-building. This focus has often fostered dependency on foreign assistance, obstructing Africa’s journey toward self-reliance and economic growth. Through examining the impacts of this approach, it becomes clear that while short-term relief has mitigated crises, it has also stunted the development of resilient institutions, local industries, and skills—factors essential for Africa’s self-sufficiency.

Short-term relief, including food assistance, emergency health interventions, and disaster response aid, is crucial during humanitarian crises. However, when it becomes the primary mode of aid delivery, it creates a cycle of dependency. For instance, the World Food Programme (WFP) frequently provides emergency food assistance across African nations facing drought, conflict, or economic instability. While this approach undoubtedly saves lives, it also limits the incentive for governments to invest in agricultural systems and food production infrastructure. Over-reliance on food aid can ultimately discourage local agricultural development, undermining the continent’s ability to feed itself.

Moreover, in response to disease outbreaks like Ebola and HIV/AIDS, international efforts have often focused on emergency responses rather than building sustainable healthcare systems. During the West African Ebola crisis of 2014–2016, substantial aid poured in from governments, non-profits, and international organizations. While it effectively curbed the spread of the disease, few long-lasting improvements were made to health infrastructure in the affected countries. The reliance on international medical teams, instead of strengthening local healthcare capacities, limited the region’s preparedness for future health crises.

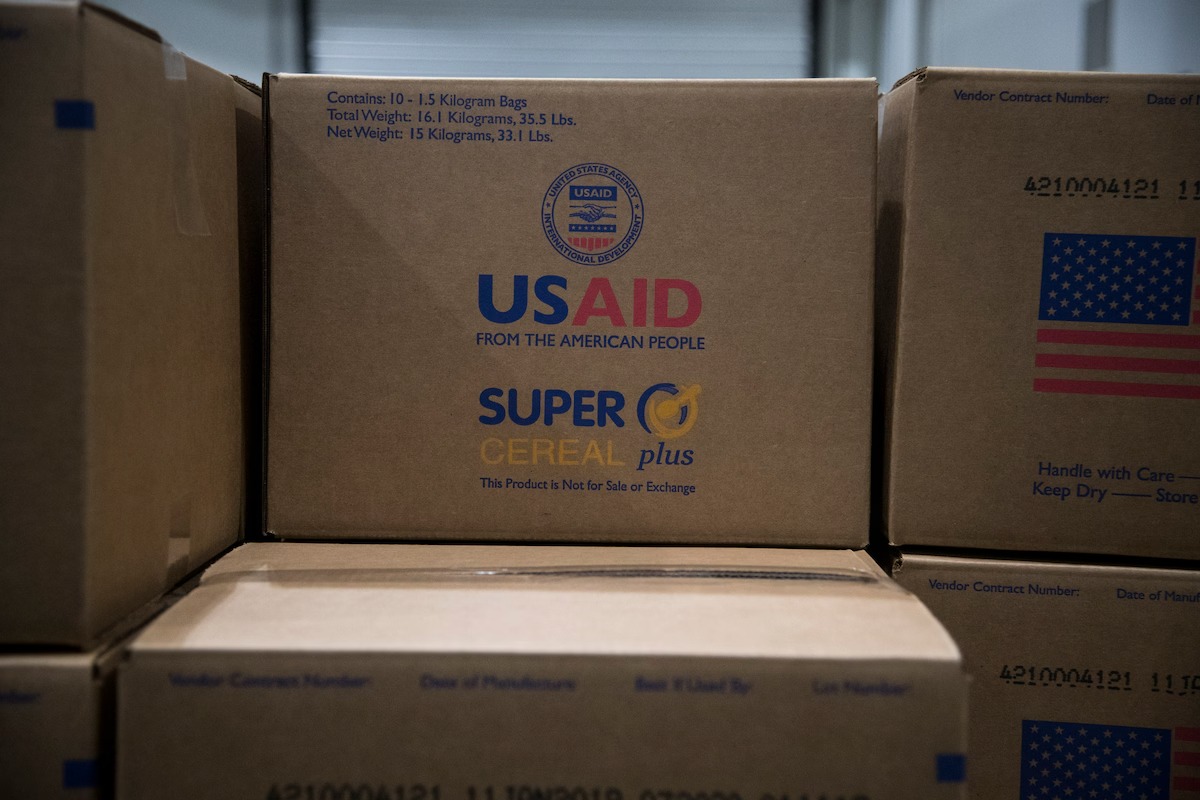

A long-term capacity-building approach focuses on developing Africa’s human capital, institutional resilience, and economic independence. In contrast, continuous short-term relief erodes self-reliance by creating expectations of outside assistance. An example is the persistence of healthcare aid in countries like Malawi and Zambia, where funding from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the Global Fund has been vital for battling HIV/AIDS. While life-saving, this assistance has also inadvertently stifled domestic health budgets and the development of sustainable healthcare financing, leaving these countries highly vulnerable should this aid decrease.

Dependency on aid has also inhibited democratic and institutional development. In many African countries, leaders have depended on foreign aid to finance public services, allowing them to avoid accountability to their citizens. Countries such as Uganda and Ethiopia have faced accusations of using aid for political gains or military expenditure rather than for sustainable development projects. When governments depend heavily on aid, they have less incentive to develop robust institutions that can provide for their people independently.

The focus on short-term relief also affects Africa’s economic development. For instance, foreign aid has often been directed toward large-scale infrastructure projects led by foreign contractors. While these projects, such as roads, schools, and hospitals, meet immediate needs, they often do not prioritize local employment or the transfer of technical skills. This trend is evident in the construction of infrastructure in Sub-Saharan Africa by Chinese companies, often funded through Chinese loans or aid packages. These projects are mostly built by Chinese labourers, meaning that the local workforce gains little experience, and the economies of host countries accrue minimal long-term benefits. Additionally, such arrangements have frequently led to debt dependency, as African countries face challenges in repaying loans due to their failure to achieve the expected economic growth.

Further, foreign aid has been directed into creating and maintaining non-governmental organizations (NGOs), which often parallel or even supplant government services. As a result, NGOs have become essential providers of services like education, health, and even clean water in many African countries. However, when NGOs fulfill these roles, it weakens state capacity and reduces government accountability, as these critical services are perceived as the responsibility of external actors rather than national governments.

To move from dependency to self-reliance, a paradigm shift is essential. Aid programs should increasingly focus on long-term investments that build the capacity of African nations to manage their resources, solve their problems, and foster local entrepreneurship. An example of a successful shift toward capacity-building is the African Union’s Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA), which seeks to develop transcontinental infrastructure, enhance connectivity, and increase intra-African trade. PIDA emphasizes collaboration with African governments and local industries to build infrastructure projects that serve the continent’s long-term economic goals rather than relying solely on external contractors or temporary fixes.

Additionally, the Green Revolution initiatives in Ethiopia and Rwanda, which focus on improving agricultural productivity and food security, illustrate how investing in local farming techniques, seed quality, and farmer education can reduce dependency on food aid. By focusing on the training and empowerment of local farmers, these programs have helped strengthen food security and promoted economic growth within the region.

While foreign aid has been invaluable in addressing immediate crises across Africa, its emphasis on short-term relief has often hindered sustainable development. By fostering dependency rather than self-reliance, aid has sometimes undermined Africa’s ability to progress toward economic autonomy. However, recent initiatives focused on capacity-building and empowering local institutions illustrate a path forward. By reorienting aid toward sustainable development, the global community can help African nations achieve their potential, build resilient economies, and eventually break the cycle of dependency.

References:

1. Moyo, D. (2009). Dead Aid: Why Aid Is Not Working and How There Is a Better Way for Africa. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux.

2. Easterly, W. (2006). The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good. Penguin Press.

3. International Development Research Centre. (2018). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Aid: The Case of African Countries.

Leave a Reply