Your cart is currently empty!

The Legacy of Colonial Borders and Imposed Governance on Africa

By Nathan Kiwere

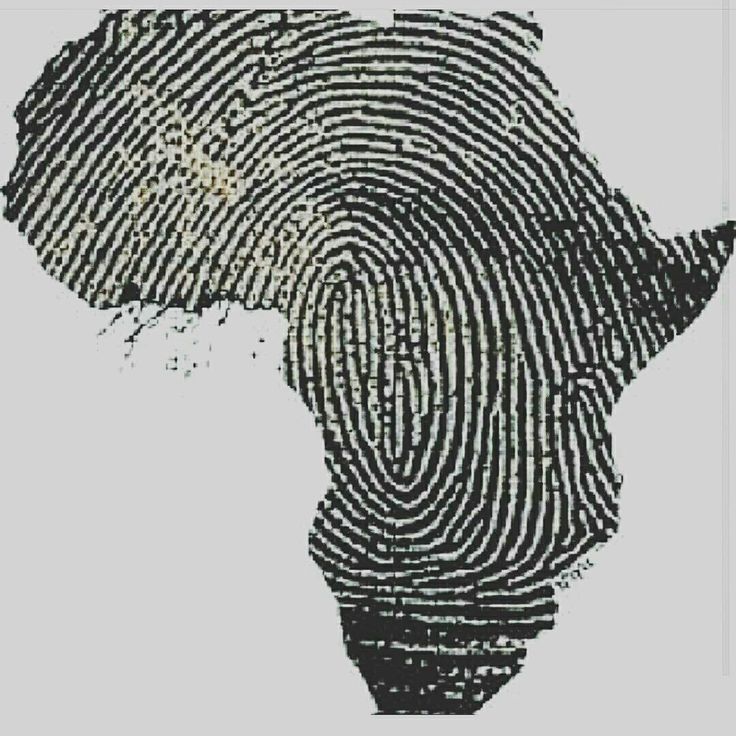

The exploitation of natural and human resources, arbitrary borders, and imposed systems of governance at the expense of well-practiced cultural, social, and political life in Africa denote a colonial legacy. The partitioning of the African continent by European colonial powers in the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885 was a statement of their economic and geopolitical interests, which completely disregarded the different ethnic, linguistic, and cultural landscapes that had grown over the centuries. The boundaries they thus set, together with the governance systems they imposed, have resulted in a complex and often problematic legacy that continues to haunt Africa to this day. These artificial borders and foreign governance models disrupted pre-existing African societies, sowed the seeds of conflict, and created problems in nation-building, political stability, and social cohesion across the continent.

Apparent in most colonial borders is that they often split communities, ethnic groups, and kingdoms into either putting diverse cultural groups together into one political entity, or, alternatively, fragmenting similar societies across different territories. For example, the Ewe people were divided between Ghana and Togo, while the Somali were divided between Somalia, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Djibouti. This did not only disrupt cultural cohesion but also formed lasting challenges to African governments that aspire to have one national identity within these artificial boundaries. As historian Basil Davidson explains, “Africa’s boundaries are quite unlike those of Europe in that they bear little relation to the natural features of the landscape or to the social organisation of the African peoples” _x0007_. The disregard for cultural and ethnic boundaries has been a fuel to conflicts across the continent, evidenced by the almost five-decade-long civil war that finally resulted in the secession of South Sudan in 2011. All these were rooted partly in the colonial era boundaries that lumped together ethnically and religiously diverse populations with remarkably different histories and governance preferences.

Along with artificial borders, another imposition was that of the incompatibility of Western governance models imposed on most indigenous African governance structures by colonial powers. Most of these were highly centralized and therefore very authoritarian. This sharply contrasts with the traditions of governance in many African societies, which are more decentralized, mostly consensus-based, and tend to be participatory. An example would be pre-colonial Rwanda, where the social setup among the Tutsi, Hutu, and Twa peoples was quite fluid, disrupted under Belgian rule. They institutionalized the divisions among them and favored the Tutsi as a superior class, thus sowing the seeds of disharmony that contributed to the genocide of 1994. In reinforcing this artificial social stratification and applying it in a manner by which to base governance, the colonial administrators laid the ground for future conflicts between such groups, aside from undermining indigenous governance structures.

Another good example is that of the Igbo people in Nigeria, where there was a stateless society with decisions made by councils and assemblies. The British nonetheless imposed indirect rule through the local chiefs even on communities that did not have hierarchical structures. This created immense friction and confusion because the chiefs appointed by the British were often viewed as illegitimate and thereby led to a disintegration of indigenous structures and a lack of trust in governance. Such impositions also bred resistance movements whereby people tried to reclaim their traditional forms of governance and identity marginalized by the colonial order.

Artificial borders and foreign models of governance have resulted in lingering effects on these countries well into the post-colonial era, with African countries grappling with border disputes, ethnic tensions, and governance challenges. In various countries, like Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Ethiopia, recurring conflict has emanated from a multiethnic state in arbitrarily drawn borders. For example, in Nigeria, deep-seated differences between the northern Hausa-Fulani and the southeastern Igbo and southwestern Yoruba have over the years aided the cause of political strife and at times erupted into violent conflict. These can be traced back to colonial policies that, for administrative convenience, treated Nigeria as one single country despite its highly multilineal culture.

Besides, the centralist governance models taken up during colonial rule had already set in, and after independence, continued to be embossed on the political systems of many African countries. The underlying tendency towards authoritarianism, centralization of power, and bureaucratic control thus reflects the legacy of the colonial governance system. Leaders like Mobutu Sese Seko from Zaire, now called the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Idi Amin from Uganda established authoritarian regimes emulating the style of the colonial administrative system. This factor works against democratic governance, increases corruption, and thereby limits inclusive political institutional development to effectively tackle the diversity of Africa.

Finally, the artificial borders and the imposed governance systems that were part of the colonial legacy have weighed upon and continue to shape Africa profoundly and caustically. In so culturally and socially making the continent a chosen site of human history, the colonial powers literally created states characterized by ethnic divisions and political fragmentation. In this respect, post-colonial African countries continue to face such challenges as managing ethnic diversity, fostering national unity, and building systems of governance in tune with their cultural traditions. In most respects, this calls for reimagining African governance to reflect indigenous values and creating frameworks for cooperation across artificially imposed borders. Coming to terms with, and hopefully finding redress for, the injustices perpetrated in these formative years is the only way a more stable and coherent future for the continent can be assured.

References

– Davidson, B. (1992). The Black Man’s Burden: Africa and the Curse of the Nation-State. New York: Times Books.

– Mamdani, M. (1996). Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton University Press.

– Meredith, M. 2011. The Fate of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence. Public Affairs.

Leave a Reply